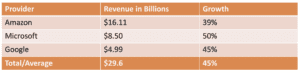

All three of the leading cloud computing providers are now large – and rapidly growing – businesses.

It’s hard to know exactly how large Azure is, since Microsoft lumps it into a cloud services category that includes Office 365, but I arbitrarily assigned half of the category’s Q3 revenue to it; it might be larger or smaller by one or two billion dollars (Microsoft did announce that Azure had grown 50% in the quarter, so its number in the second column is accurate). In total, the three did just under $30 billion in revenue this past quarter, with a clear path to $120 billion in revenue over the next year.

AWS, the largest of the three, is now on a $60 billion annual run rate. Its growth rate – which captures the direction and velocity of this industry shift in a single number – was 39% for the quarter, and represents its fourth consecutive quarterly increase. It’s easy to acknowledge this achievement, but hard to recognize just how impressive it is. AWS is – by far – the fastest growing technology company of its size in history. In fact, it might be the biggest, fastest growing company in human history, with no sign of slowing down on the horizon.

It seems clear that AMG’s growth path will continue for the foreseeable future. The shift to public cloud computing is the dominant trend in the industry and it’s only going to get bigger going forward.

The Role of Cloud Has Changed

In its early days, cloud computing served the most adventurous users – early adopters drawn by its easy access, usage-based pricing, and low cost. There was very clearly a ton of pent-up demand for this type of service.

The startup community has been transformed by cloud computing. In the old days, standing up a new online service required significant capital investment, and huge growth – the hope of all startups – necessitated massive capital requirements to stand up even more infrastructure. The cloud changed all that. Today, a personal credit card can launch a new company, and scaling it requires far less capital. Predictably, this has resulted in an explosion of new companies exploring innovative ideas.

Likewise, as enterprises began to launch digital offerings (and compete with startups invading their space with those new online services!), the groups responsible for these offerings naturally followed the startup community onto the cloud.

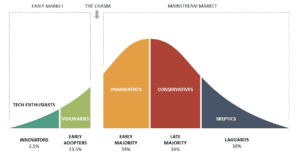

Both of these types of users would fall into the category of innovators and early adopters, as shown in the traditional market segmentation diagram associated with “Crossing the Chasm.”

We are now well past that stage of cloud adoption. Mainstream enterprise and government use – represented as pragmatists and conservatives in the above chart – now accept public cloud computing as a viable choice: capable, secure, and cost-effective.

However, many enterprises have moved beyond viewing the cloud as a viable choice, one solution among several options. I’ve heard of many companies changing their strategy to define cloud as their preferred deployment location, with some going so far as to develop a plan to empty their data centers completely and operate everything in the cloud.

This is clear evidence of a changed cloud market, with adoption having moved to pragmatists and even conservatives, as those companies confront the limitations of their traditional on-prem preference.

And, as the chart above illustrates, these two market segments represent the majority of users, which explains the boffo financial results of the cloud providers. The providers are benefiting from cloud finally being accepted by mainstream enterprises and becoming an acceptable deployment choice for every kind of application, not just “digital” ones.

The Cloud Future: Full Speed Ahead

Given the results of the quarter, and the evidence of increasing enterprise appetite for cloud computing, the obvious question is “how tall will this tree grow?” Many people over the past few years have predicted slowing growth for AMG; after all, they are huge businesses and intuition and past industry experience would seem to imply that they would start to see a drop in their growth rates.

Set against that, of course, is the fact that AWS has actually increased its growth rate for each of the last four quarters. Some would, I suppose, attribute that to pandemic-induced growth. Microsoft’s CEO Satya Nadella said “The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the digitisation process by at least a decade,” which obviously meant good news for AMG. Consequently, one might think of the past year as a temporary upward blip in a downward growth trend, given that AWS had actually seen a decrease in its growth rate in the eight quarters prior to Q220.

Part of what affects growth is how large a market an offering aims at. In any new market, growth is easier early on when the highest payoff sales are made; later in a market adoption cycle sales get more difficult as lower-productivity applications of the new technology are made. Naturally, growth slows when the benefits of purchase are lower.

This means that the overall potential for AMG sales as well as what their growth rate is likely to be going forward rests a lot on just how much opportunity there is in becoming the de facto enterprise infrastructure environment. In Silicon Valley-speak, the question is how large is the TAM — the Total Addressable Market?

One often hears the phrase “the enterprise market is a trillion dollars.” A good, albeit imperfect, way to assess this phrase’s accuracy is to look at the estimates put out by technology analyst firms. They survey large numbers of enterprises, perform some number-crunching, and develop overall market size estimates.

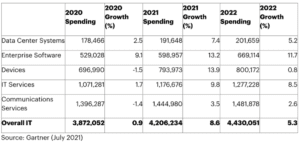

Gartner recently published its estimates for 2021 and 2022 as can be seen in the table below.

Adding its spending categories of data center systems and enterprise software gives a rough idea of how much on-prem spending enterprises do. For 2021, enterprises will spend just shy of $800 billion; for 2022, they will spend $870 billion, which isn’t that far off from the trillion dollars conventional wisdom.

So is a trillion dollars the TAM that AMG have? If their yearly run rate is around $120 billion, it would seem they have quite a bit of market yet to swallow.

However, this underestimates how much spend AMG can address. Data center equipment is typically on a three to five year depreciation cycle, while enterprise software carries ongoing maintenance and upgrade costs across a similar period. So AMG’s TAM is not one trillion dollars, but the sum total of what enterprises spend across the depreciation/support/upgrade cycle, which is more like $3 to $5 trillion.

In other words, there’s plenty more market that AMG can go after, and plenty more room to grow, and to grow at high rates.

These TAM estimates are based on one for one takeout — a dollar not spent on traditional infrastructure can be spent on AMG. That completely overlooks the potential increased addressable market made possible by the reduced friction and usage-based pricing offered by AMG.

The scale of the unaddressed market is typically overlooked and unexamined. But a clue to what happens when reduced friction and lowered costs meets untapped demand can be found in the theories of a 19th century British economist — William Stanley Jevons, whose “Jevons Paradox” I wrote about in 2015.

In his study of British coal consumption, Jevons noted that people actually consumed more coal as coal prices dropped, which is somewhat counterintuitive. After all, if something gets cheaper, wouldn’t people take the savings and buy something else? In fact, Jevons found they bought more coal and used it for purposes they couldn’t previously afford.

Consequently, it’s plausible that AMG face a TAM of something like $10 trillion — $3 trillion to $5 trillion of existing traditional spending, and $5 trillion to $7 trillion of new computing appetite previously unserved by historical IT consumption practices.

I believe that enterprise uptake of cloud computing has lots of room for growth, and I predict that AMG growth rates will increase as the benefits of cloud computing get better understood and more and more use cases (i.e., previously unaddressed demand a la Jevons Paradox) are discovered. The torrid growth we’ve seen over the past few years is nothing more than a prologue to even headier growth in the future.